“Hey! What happened to the little girl on the right side of the shot?”

I want to believe, for dramatic effect only, that there was a time when Hollywood talent agents would pray I wouldn’t cast with them, especially for children or old people. The reason: two incidents that happened quite close to each other during different TV productions.

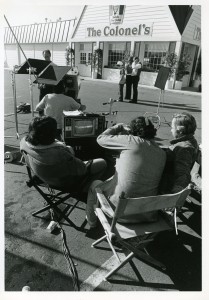

The first occurred at a Clorox 2 commercial I shot with director Victor Haboush on his Santa Monica Boulevard stage in Hollywood.

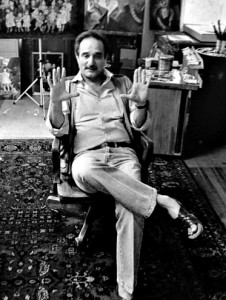

Victor Haboush, as I remembered him. We became good friends over the years.

The commercial starred a mother and her three young daughters. We cast a woman and three girls who looked similar enough to be from the same family. Coincidentally, two of the girls were sisters.

We started rolling film around 9:30 in the morning. The scene was designed to show the mother and her three daughters in clean clothes standing in front of a 15-foot tall “before” photo of the four of them in dirty clothes. Looking from the camera, Mom was on the left and the three girls were step-laddered on her right starting with the youngest and ending with the eldest; the same positions displayed on the giant “before” photo behind them.

The shot started with a close-up of the mom as she spoke one line and then widened out to reveal the four of them looking clean and happy in front of the enlarged photo.

It was either the third or fourth take when it happened. The producer, the clients and I were watching the videotape-assist monitor as the camera widened out and held its position. As we watched, we could see the eldest girl start to waver back and forth and suddenly fall forward. Victor Haboush, who was operating the camera, turned to us and said, “What happened?” I looked to the stage and saw the girl lying face down.

She passed out and slit her chin open on the concrete stage floor. She was given first aid to stop the bleeding and then a member of the crew drove both her and her mother to a nearby hospital emergency room.

No one could understand why she passed out. It was early in the shoot, the lights were not hot and she was just standing. Perhaps the excitement of getting the part and being on stage overwhelmed her or maybe she forgot to eat breakfast. Whatever it was, we never found out.

After the hubbub, the first thought was that we would have to cancel the shoot. However, Victor pointed out that luckily she was the furthermost person to camera right on stage and in the photograph. So by changing the shooting angle, we could effectively cut off the right side of the photo. After repositioning both the camera and the mother with only two daughters now, we continued to film.

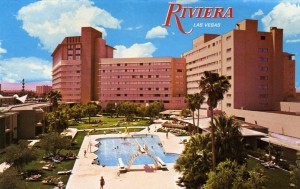

To add to the dismal start of the day, at dinner that night, Victor related another incident that happened to him while shooting a commercial by a hotel swimming pool a few months earlier.

One of the hotel guests, an elderly man, came down for a late morning swim. Because they weren’t using the pool in the shot, the production crew told the man it was all right to swim.

No one paid particular attention as he swam his laps. At one point, someone turned around and saw him floating face down. Crew members dove in and pulled him out. Someone performed CPR. When the paramedics arrived, it was determined he had a fatal heart attack and was dead before he was pulled from the water.

Camera! Action! Cut!

“Eight-six the raven!”

About 6 months later, we were filming a Pacific Telephone commercial. The director was a Type A personality with a loud voice to match. He believed that the only way to get a performance out of his actors and his crew was to shout them into action.

Professional raven preparing himself for the next take.

To illustrate my point, the commercial called for a live raven. You’ll have to believe me when I tell you the raven was a Hollywood pro, who had done a number of films. Even with all of the surrounding activity and noise, it would sit calmly on its perch minding its own business, probably thinking up birdbrain ideas. However, each time the director would yell action at the top of his lungs, the bird would go crazy; flipping upside down on the perch, flapping its wings wildly and screaming. After a number of takes, we had two options: either get rid of the director or eighty-six the raven. As I look back, I think we should have chosen the first option.

We used a wonderful old character actor with a very unique voice by the name of Lou Krugman for the principle part. For some reason, during the initial casting and call back session, the director had Lou read the copy as if performing a Shakespearean play. He never corrected Lou nor directed him to speak the lines less dramatically.

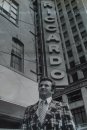

Lou Krugman as he appeared in the movie “Irma LaDouce.”

Lou continued this overly dramatic reading as we began filming the commercial. About half way through the scene, Lou was becoming visibly nervous and upset as the director, in a voice that continued to increase in volume, pushed him to speak his lines faster.

Lou started to forget his lines. It happens; actors and actresses freeze. They concentrate so hard on their parts that they have a temporary lapse of memory.

But it continued. Soon I began feeding Lou each line, which might have been only three words long. But as soon as the camera would start rolling, he would get the first word out and forget the next two.

Lou claimed he was nervous because it had been a while since he performed on camera but wanted to continue on if I would help him with the lines. By this time the loud-mouthed director, who I believed at the time was probably the cause of Lou’s nervousness, had quieted down. It wasn’t until Lou finished his part that he confessed he wasn’t feeling well. He reluctantly agreed to go to the hospital and get checked out. A production assistant drove him.

We continued shooting the other performers and their scenes. Towards the end of the day, we were informed that Lou was indeed ill during the shoot and would be staying in the hospital overnight for observation. Everyone felt terrible, especially because no one realized he was having a medical issue.

Fortunately, Lou recovered completely. Over the years, I used him many times as a voice-over talent and often saw him in TV commercials and heard his voice on many radio spots. We corresponded regularly and would have an occasional lunch when I came to Hollywood.

The last time I saw Lou was on stage at the Raleigh Studios where I was shooting some commercials with Vincent Price. Lou and Vincent did a radio show together back in the 1930s and Lou wanted to give Vincent an audiotape of the show. So I invited Lou to the set. He stayed the day. In between takes, he and Vincent spent hours reminiscing about the radio show and people they knew in the business at that time.

Lou passed on a year or so later. A unique person and a unique voice, silenced.

Animal Crackers

Lou Krugman was cast to play the part of Boris, an old fortune-teller. Near the end of the commercial, Boris is seen dialing the phone and saying, “Hello daddy.” There is a cut to a white-haired, even older fortune-teller dressed in a tuxedo with cape sitting in a chair with a phone to his ear responding, “Boris.” An owl is perched on the back of his chair. As if on cue, the owl coincidentally, says “Who” immediately after the old fortune teller said, “Boris.” The actor, an old pro, looks over his shoulder at the owl and immediately ad libs, “My son.”

Obviously, we edited this scene into the finished commercial and we didn’t have to pay the owl for the speaking part.

Got a production story? Share it. Add it as a comment to this post.