I like eating out.

When I was working full-time at ad agencies, it was not only one of the fringe benefits of my job; it was how we did business and made connections. I was either being treated to lunch or dinner by a film rep or production company or using an expense account to take a client out. While I could probably spend hours regaling my dining experiences at many of the classic old time and hip ” in” restaurants in Chicago, New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, I thought I’d share just a few unforgettable incidents that are as fresh in my mind today as when they happened.

One night Chuck Sheldon, the Executive Producer at Foote, Cone & Belding San Francisco, and I made arrangements to meet for dinner at the Steak Pit on Melrose Avenue in L.A. I had never been there. With address in hand, I drove up and down Melrose neck craned looking for the restaurant, but I couldn’t find it. How hard could it be to find a restaurant called the Steak Pit? So I parked my car in the block where it should have been, found a pay phone (pre-cell phones in those days) and called the restaurant. They told me they were on the corner only a half block away. How could I have missed it?

I walked the half block and looked around the intersection. On three of the corners were three businesses that were clearly not restaurants. Across from me, on the fourth corner, stood a one-story building with no sign, blackened out windows, and a recessed red steel door illuminated by a bare light bulb. It didn’t look like a restaurant.

I tried the door. It was locked. I stared at the piece of paper in my hand. I couldn’t understand how I messed up the directions. For some reason, I decided to knock. Nothing happened. I waited a minute and was about to leave when suddenly the door opened and a man in a red waiter’s jacket asked: “The name, please?” I said I was meeting Chuck Sheldon. He motioned me in.

I entered into what I can only describe as someone’s Midwestern, knotty pine paneled, basement rec room with a bar along the wall. This was not what I was expecting, but apparently it was the Steak Pit. Since I was early, I sat at the bar where the owner Joe Gothard served me a drink. As we talked, I mentioned that I had difficulty finding the restaurant. He told me his customers seemed to like the discreetness of no signage and blacked-out windows. Made me wonder who his customers might be.

The Steak Pit was located on the corner of Melrose and Sierra Bonita Avenues. I’m not sure what business occupies the space today, but it looks like the red steel door is still in place.

After Chuck arrived, we were shown to the dining area. It was quite small, eight or ten tables at most. An original portrait of Amelia Earhart hung over the fireplace. (According to Chuck, Joel Squier, a producer friend of ours, tried to purchase the portrait from Joe on numerous occasions, but never succeeded.) Except for a couple at a table in the corner, we were the only other customers.

The menu was simple: lamb chops, or a 16- or 22-ounce New York Steak. A salad, sliced beefsteak tomatoes and a frying pan of grilled onions unceremoniously dumped onto a large plate in the center of the table rounded out the dinner. Aside from some sliced French bread and butter, I don’t remember there being much else on the menu. The steak, just off the grill, continued to sizzle on the plate for at least 5 minutes after it was served. This had to be the best steak I ever tasted since moving from Chicago with its melt-in-your-mouth corn-fed beef.

The couple left about a half-hour before we finished dinner. Joe joined us while we had coffee. He told us to always call and make reservations because the restaurant was open sporadically depending on the number of reservations.

And he wasn’t kidding about reservations because the famous story about the Steak Pit concerned a music composer friend of mine. He brought his clients to the restaurant after an early evening music session. He knocked. The waiter, who happened to be Joe’s son, opened the door and said: “The name?” The composer, who was a regular, gave his name and asked if he could get a table for five. After greeting the composer by his first name, Joe’s son apologetically replied, “reservations only” and quietly closed the door.

The composer’s clients were dumbfounded. The composer told everyone to just wait at the door. He walked a half block to probably the same pay phone I used. He dialed the restaurant and made reservations for five, in five minutes.

He returned to the restaurant and knocked on the door. The waiter answered. The composer gave his name. The waiter remarked that they were a little early but could come in and wait at the bar until their table was ready.

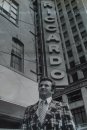

“That Toddlin’ Town”

In the 1960s and 70s, Riccardo Restaurant and Gallery was probably the number one “Mad Men” advertising and PR luncheon hangout in Chicago. It was located on Rush Street almost in back of the Wrigley Building. Aside from ad people, the restaurant and bar were frequented by such Chicago newspaper and television personalities as Len O’Connor, Mike Royko, Irv Kupcinet and Studs Terkel.

When you lunched at Riccardo’s, you could over a period of time see and meet just about everyone in the Chicago ad business. In fact, it was so populated with ad people that no one dared talk shop because you could never be sure if someone from another agency was sitting behind you or at the next table.

The bar at Riccardo’s was quite unique. It was in the shape of a painter’s palette with its narrow end facing a high curved wall. When Ric Riccardo, Sr. founded the restaurant, it doubled as an art gallery and gathering place for local artists. Riccardo hired six well-known artists to paint six over-sized, 4- x 8-foot high murals representing the “Lively Arts” to hang on the curved wall in back of the bar. He painted the seventh. (Riccardo also owned Pizzeria Uno where reportedly he and co-owner Ike Sewell invented Chicago’s world-famous deep-dish pizza in 1943.)

Three of the seven “Lively Arts” murals grace the curved wall.

Because of the number of ad people who gathered at Riccardo’s, it was a natural hangout for art, photography and film reps. One group of everyday regulars had their assigned places at the bar and more likely than not were either entertaining an agency art director or producer or sending drinks to someone’s table.

The same reps sat at the same bar stools day in and day out. Nothing seemed to change. For example, after three years in San Francisco, I returned to Chicago on a business trip. I arranged to have lunch at Riccardo’s with Jack Sheasby, a director friend of mine. I arrived a little early, so I headed to the bar. It was as if I never left; all the reps were sitting in their appointed places. As I walked in, one rep turned, saw me and said, “Hey. Where have you been? Haven’t seen you for a couple of weeks.”

Joel, Joel, Joel

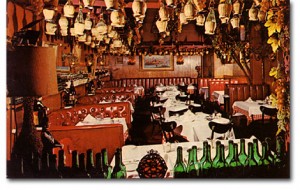

I was first introduced to Sal’s Martoni’s Restaurant in Hollywood after a late evening music recording session. I was told it was the only full-service restaurant in the Hollywood area that kept its kitchen open past 10 p.m. aside from Cantors Deli and some late night diners. It was located on Cahuenga Boulevard just across from the famous Wally Heider Recording Studio.

My funniest evening at Martoni’s took place at the long table in front, just behind the green wine bottles.

It was a Italian restaurant opened by Ciro (Mario) Marino of Marino’s Restaurant on Melrose and was now run by his son Sal. I didn’t know it at the time, but Martoni’s had been and still was a big hangout for singers and music execs, such as Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Sonny Bono, Sam Cooke, Phil Specter, The Beatles, the Grateful Dead and many more. Unaware of its past and present star-studded history, I simply thought of it as a great place to go for delicious Italian food, especially my favorite Italian dish: Scungilli (an ocean mollusk) with penne pasta in a spicy marinara sauce.

The evening I remember most at Martoni’s was a dinner with a group of people, which included myself, a producer friend Joel Squier, and Joel Goldsmith from Glenn Swanson Studios. Aside from a hilarious evening of all three Joel’s not being sure to which of us any question was being directed, it was capped off when the waiter came to the table and announced a phone call for Joel.

The waiter had no idea why everyone at the table simultaneously burst out laughing.

Please Eat Somewhere Else

Another Chicago restaurant that I frequented was Louie’s Cantonese Restaurant on Rush Street toward the south end of the nightclub area. Agency people, film directors, art reps, music composers, musicians, nightclub entertainers, singers and actors at one time or another ate at Louie’s. It was a Rush Street institution made so by Louie himself. With the wink of an eye or a turn of a phrase, his wry sense of humor could quickly transform his stoic look into a beaming smile.

I remember on a particularly slow restaurant day asking Louie if he wanted to join us for lunch at our table. He quipped in broken English, “What? Eat here? You think I crazy?”

The restaurant was a favorite of music composer and arranger Bobby Whiteside. I used Bobby quite often to compose music for the Kentucky Fried Chicken jingles I wrote while at Leo Burnett. He recorded almost exclusively at Universal Recording Studios on East Walton, which was around the corner from Louie’s. Needless to say, we ate many lunches and dinners there.

One afternoon Bobby, my art director partner Glenn Fujimori, and I were having a late lunch at Louie’s after a morning recording session. As usual, a big part of lunch was joking around with Louie and the one-upmanship involved. Bobby was feeling smug because he believed Louie had no retort to his last joking remark.

When we were ready to leave, it seemed to take longer than usual for the check to arrive. Normally the check came on a plain white saucer with fortune cookies on top. This time, however, we each received our fortune cookie on individual saucers.

A narrow strip of paper hung out of one end of Bobby’s cookie. Curious, he pulled the paper out. Carefully hand-printed on the small strip were the words: “Confucius say: Please go eat somewhere else.”

Louie peered from behind the circular window of the swinging door that led to the kitchen, his eyes laughing in back of his thick, black-rimmed glasses.